The I Ching – how to use coins and sticks

Instructions and thoughts on how to use both methods to find a hexagram in the I Ching

Some years ago I finally sat down to learn how to consult the I Ching (or the Ji Ying if you prefer) using yarrow stalks. Or rather, yarrow stalk substitutes. It turned out that it was the wrong time of year; nothing resembling yarrow grows in our garden and even if there had been, I’m not really patient enough to wait for the stalks to dry out. So, this being a Time Before The Virus Came, I trudged around Hammersmith High Street near my day job until I found boxes of wooden pick-up sticks on sale in a branch of Tiger. Two boxes = fifty fake yarrow stalks and a bunch of spares.1

Using coins to select a hexagram

I’ve been a devotee of the Richard Wilhelm I Ching for a long time and Jung’s famous introduction has explained the mechanics of the three coins method to millions of devotees over the last century. Jung explains how the querent tosses three coins and assigns a value of three to each coin that lands heads up and two to coins landing with tails facing up. A score of seven generates a ‘yang’ or unbroken line whilst nine gives a ‘moving’ yang line. A moving line means a line about to flip into its opposite. Other sources call them ‘young’ yang and ‘old’ yang. A score of eight gives a broken (yin) line and six a moving (young) yin line. Young yin is is of course close to turning into a yang line. An old yang line is indicated with an ‘o’ written in the middle of the line. An old yin with an ‘x’.

Got all that?

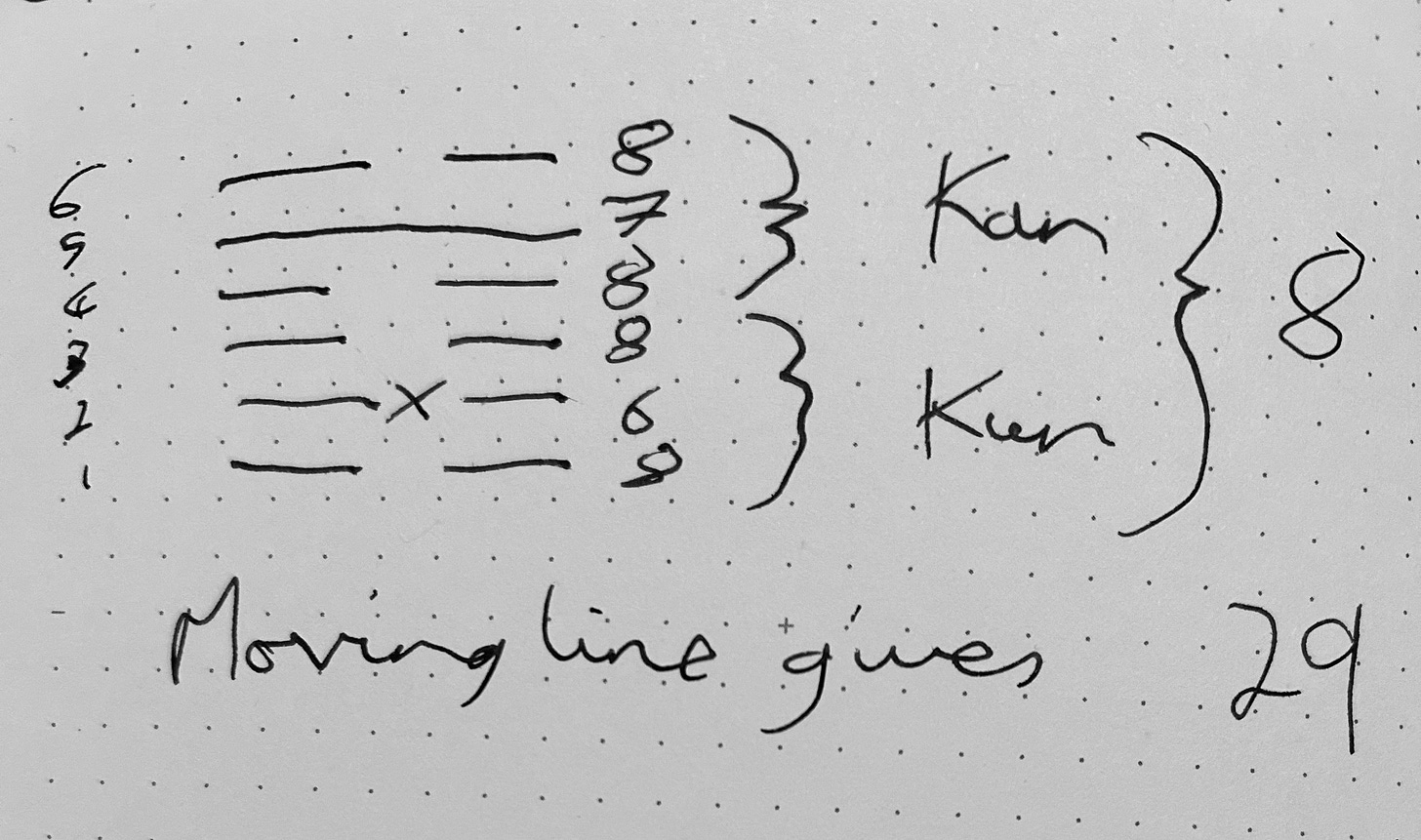

The first line is the bottom of a hexagram. The ideograph is then built up from the ‘ground’ with the process repeated a further five times, generating one of 64 possible variations, along with a potential second hexagram should the one of more of the lines be ‘old’. Here’s an example:

Line one (the bottom line remember) had heads, heads tails = 3 + 3 + 2 = 8. This gives us young yin in the first line.

Line two had tails, tails, tails = 2 + 2 + 2 = 6. This gives us old yin in the second line.

Line three had heads, heads tails = 3 + 3 + 2 = 8. This gives us young yin in the third line.

Line four had heads, heads tails = 3 + 3 + 2 = 8. This gives us young yin in the fourth line.

Line five had heads, tails tails = 3 + 2 + 2 = 8. This gives us young yang in the fifth line.

Line six had heads, tails, heads = 3 +2 + 3 = 8. This gives us young yin in the sixth line.

You’ll see we have two hexagrams to consult - 8, Pi (Closeness or Side by Side in John Minford’s excellent translation) and 29 (Abyss or The Pit) . If you don’t have your own copy, the Wilhelm/Baynes version is widely circulated online but its worth investing in a more recent translation - research and understanding has come a long way since 1924 when Wilhelm published his landmark translation (though it’s still seen as wholly valid and I still regularly consult it).

In nearly all transactions, the Hexagrams are structured as follows:

Firstly, you’ll see the Name of the Hexagram and its two component trigrams (in our example, Kan (Abyss) and Kun (Earth)

This is usually followed by the Judgement - a very ancient explanation of the meaning for the Hexagram. Generally needs clarification

Then comes the Image - another ancient explanation. Often needs even more clarification!

After this comes the various commentaries, ancient and modern from Chinese scholars of classical times or modern translators, that have built up around the I Ching over the millennia since it first emerged from even more ancient practices of sortilege with bones and tortoise shells

Lastly, we have commentaries on the Lines - if any of the lines are ‘old’, these texts should also be consulted. They’ll be presented as ‘Six in the First Place” or similar. And, yes, I do wonder if Jimi Hendrix was probably familiar with the I Ching - it’s the only explanation I have for his song title “If Six was Nine”

If a second Hexagram has been generated through a moving line, only the Judgement, Image and initial commentaries are read.

Here’s our example, taken from the Wilhelm/Baynes edition:

8. Pi / Holding Together [union]

above K'AN THE ABYSMAL, WATER

below K'UN THE RECEPTIVE, EARTH

The waters on the surface of the earth flow together wherever they can, as for example in the ocean, where all the rivers come together. Symbolically this connotes holding together and the laws that regulate it. The same idea is suggested by the fact that all the lines of the hexagram except the fifth, the place of the ruler, are yielding. The yielding lines hold together because they are influenced by a man of strong will in the leading position, a man who is their center of union. Moreover, this strong and guiding personality in turn holds together with the others, finding in them the complement of his own nature.

THE JUDGMENT

HOLDING TOGETHER brings good fortune.

Inquire of the oracle once again

Whether you possess sublimity, constancy, and perseverance;

Then there is no blame.

Those who are uncertain gradually join.

Whoever come too late

Meets with misfortune.

[…]

THE IMAGE

On the earth is water:

The image of HOLDING TOGETHER.

Thus the kings of antiquity

Bestowed the different states as fiefs

And cultivated friendly relations

With the feudal lords.

Of this, Wilhelm notes:

“Water fills up all the empty places on the earth and clings fast to it. The social organization of ancient China was based on this principle of the holding together of dependents and rulers. Water flows to unite with water, because all parts of it are subject to the same laws. So too should human society hold together through a community of interests that allows each individual to feel himself a member of a whole. The central power of a social organization must see to it that every member finds that his true interest lies in holding together with it, as was the case in the paternal relationship between king and vassals in ancient China.”

The commentary on the second line (six, old yin) reads

Six in the second place means:

Hold to him inwardly.

Perseverance brings good fortune.

If a person responds perseveringly and in the right way to the behests from above that summon him to action, his relations with others are intrinsic and he does not lose himself. But if a man seeks association with others as if he were an obsequious office hunter, he throws himself away. He does not follow the path of the superior man, who never loses his dignity.

After that, one consults Hexagram 29, Kan, which should be read as a development of the first and as further advice on how to proceed as matters are in the process of changing - it’s the Book of Changes, remember!

Using sticks

When generating the hexagram with sticks, the principle is still the same – carry out a consistent process to deliver a more or less random output of the number 6, 7, 8 or 9. It’s just that there are a number of intermediate processes involved and the whole business takes up to fifteen minutes if done carefully. I find I use it for very significant or meaningful questions. It slows the whole process of consulting this enchanting book down. Establishing a question, holding it in one’s mind, generating a hexagram to look up – it all becomes a precise, dance-like ritual. It stills the busy mind, clarifies and deepens whatever enquiry I might intend to ask and puts me in the kind of space where I’m prepared to listen carefully. It generates an opening for whatever the Sage of the Book of Changes has to tell me.

So what does it involve?

1) Take your 50 sticks (or stalks)

2) Put ONE stick aside. You now have 49

3) Divide them into two piles

4) Take a single stick from the right hand pile and place it between the little and ring fingers of left hand

5) Pick up the left hand pile and hold in your left hand

6) Take four sticks from the pile held in your left hand and keep doing this until there are only 4, 3, 2 or 1 sticks left

7) Place the remainder between your ring and middle finger.

8) Pick up the right hand pile. Repeat the process of removing four sticks at a time until you have 4, 3, 2 or 1 sticks left.

At this point you will be holding a total of either 5 or 9 sticks. 5 is taken as equivalent to 3. 9 is equivalent to 2. Write that down!

Repeat the whole process two more times. This will give you the equivalent of the coin toss scoring for the first line of the hexagram - in our example above, 3 (from five sticks), 3 (from five sticks) and 2 (from nine sticks) = 7 which gives us a young yang (unbroken) line.

Repeat all of this for the following five lines. If you make a mistake or the numbers just don’t add up the way they should (e.g. you find you have sticks in your hand that add up to a different number than 5 or 9) start again.

You see why this can take a while? Here’s a video which may or may not help.

Is there an equivalent for the tarot? One analogue might be the complex series of shuffles, cuts, counts and deals that MacGregor Mathers set out for the Golden Dawn.

But there’s a key difference. In building an I Ching hexagram line by line, you are literally constructing an image of the universe at a specific moment in time and space from the most fundamental materials imaginable – light and dark, ones and zeros, positive and negative. I feel that the reverse is true of some methods of Tarot card selection and patterning, that single, infinitely rich sets of heterogenous symbols are broken down and simplified.

However, both tools – or books – demand seriousness. They might be playful but they never play games (unless one is foolish enough to play games with them). The main lesson of the question of sticks versus disks (as it were) is the need for stillness, slowness and to take advantage of whatever method might generate that quiet little voice from deep within that says “Here is some truth.”2.

*I could have bought dried yarrow stalks over the InterWebs but witches improvise.

Though if you sometimes have to get up in a rush and pull a single card for a clue or thread to follow through the day – that’s something the Tarot is fairly forgiving of. Within reason.

I have the Wilhelm book sitting on my shelf. You have inspired me to dust it off. Another helpful and thoughtful article. Thank you!